.200

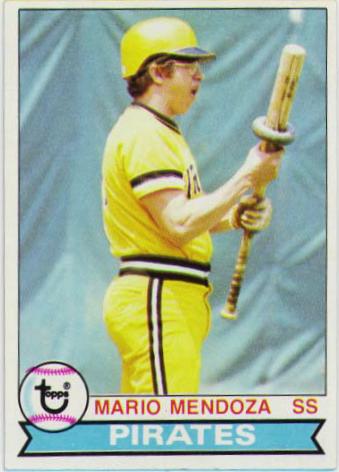

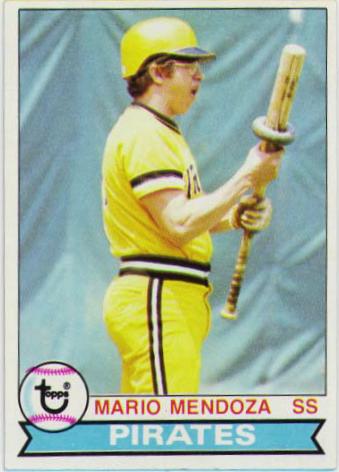

THE CURIOUS ORIGINS OF THE MENDOZA LINE

by AL PEPPER

The real deal behind baseball's coolest and most misunderstood term

According to The New Dickson Baseball Dictionary, the following is the definition of the term "Mendoza line:"

Mendoza line. 1. The figurative boundary in the batting averages between those batters hitting above and below .215. It is named for shortstop Mario Mendoza whose career (1974-1982) batting average for the Pirates, Mariners and Rangers was .215.

2. The figurative boundary in the batting averages between those batters hitting above and below .200. "When a struggling hitter pulls his average above .200, he has crossed the Mendoza Line." (Sports Illustrated, Sept. 13, 1982.) Jim Henneman (Baltimore Sun, June 7, 1994) wrote of Brady Anderson: "A few years ago, when he was struggling to stay above the Mendoza (.200) line, Anderson commanded the same strategy."

ETY Coinage of the term has been credited to George Brett, who has quoted: "The first thing I look for in the Sunday papers is who is below the Mendoza line" (Glen Waggoner & Robert Sklars, Rotisserie League Baseball, 1987. But according to Sports Illustrated (Aug. 20, 1990), the term was coined by Tom Paciorek or Bruce Bochte; broadcaster Mel Proctor (Home Team Sports telecast, Apr. 25, 1996) said Mendoza, while playing for Seattle (1979- 80) was hitting above and below .200 and that teammates Paciorek & Bochte commented on that fact in the interview, and later Brett picked up on it and used the term.

Usage Note. This clearly emerging term can have two slightly different meanings (.215 vs. .200), so it is important to make sure which Mendoza line is being referred to. However, it seems like the .200 line is used much more commonly than the .215 version.

For all practical purposes, definition 2 (the .200 version) is the only one I have seen used in context. In this work, any reference to "Mendoza Line" is also ensconced in the .200 standard.

The first time I heard the term was early in the 1988 season. Naturally, it was ESPN Sportscenter host and legendary sobriquet-fabricator Chris Berman, who uttered the words during a Sportcenter broadcast. He was using it in reference to a prominent slugger (don't ask me who), whom was struggling in the early season. From then on, not only have I heard the term used often in the sport of baseball, it has transcended into other disciplines as well.

Even before Mario Mendoza ever played, there were other terms used for a less-than-stellar hitter. In the 19th century, you could be a "tapperitis hitter" or one who hits tappers. "Can't hit a balloon" and "Can't hit a bull in the ass with a shovel" go back to the beginning of the century. There's "buttercup hitter," first used in the '30s. To not "hit one's weight" is another. You could "have a hole in your bat," be an "out man" or be a "10 o'clock hitter," meaning you hit the ball hard during morning batting practice but do little during the game. "Banjo hitter," "ukulele hitter" and "Punch and Judy hitter" all describe light hitters; however, not necessarily a totally inept batter as it has the connotation of someone who can scratch-out cheap singles. Of more recent vintage, a batter "on the Interstate" would mean that his .180 batting average would look like "I80" on old-fashioned scoreboards lights.

There were even a few precursors to the Mendoza line. The Giants of the late 1960s had the "Lanier-Mason Line", a play on Mason-Dixon Line, which suggested you were hitting in the range between Don Mason (.205 career batting average) and Hal Lanier (.228 career batting average). The Tigers had the "Ray Oyler Divide." Most likely, every Major League team had some sort of less-than-complimentary term for lackluster hitting, named after some obscure player, which came and went. But in just a span of 20 years, the Mendoza line has become so mainstream, it will most likely live as long as baseball.

Many theories abound on who first described the mythical line that separates decent hitters from marginal hitters. Pirates' fans claim legendary announcer Bob Prince came up with the term while Mario Mendoza was batting .140 one year; I doubt it. Another source credits Johnny Bench. There is even a minority, insisting that Christobal (Minnie) Mendoza is the actual Mendoza referred to in "Mendoza line." Minnie Mendoza, a consistent .300 hitter in the minor leagues during the '60s, finally made it with the Minnesota Twins in 1970. At age 36, Minnie hit .188 in 16 games with the Twins that year. Though Minnie Mendoza truly hit below .200 for his brief Major League career, no documented evidence supports the claim of anyone using the term "Mendoza line" in the '60s and early '70s.

Most credit coinage of the term to George Brett, who originally quoted in 1980: “The first thing I look for in the Sunday papers is who is below the Mendoza line.” However, according to Sports Illustrated (Aug. 20, 1990), Mendoza’s teammates on the Seattle Mariners, Tom Paciorek and/or Bruce Bochte, are the originators. Mendoza told SI that Paciorek invented the term. But Paciorek insisted otherwise, “It wasn’t my idea. It was Bruce Bochte’s. I got the credit, but I don’t want it.”

There was some credence to Brett being the originator. As far back as I can remember, every Sunday paper in the country presents the Major League batting and pitching statistics, as compiled by the Elias Sports Bureau. The format separately lists National League and American League batters in order from highest to lowest BA. Not every active player makes this list. To appear, a player must have a minimum number of plate appearances (different from an at bat) each week, based on the product of games played as of the previous Friday, multiplied by the constant 3.1. Since Mario was primarily a reserve with the Pittsburgh Pirates, he never would have appeared in this feature since he never had the requisite number of plate appearances.

However, while playing in the American League, Mario, at least for a while, was a regular and would have appeared in the Sunday tabulations for a good part of the 1979 through 1981 seasons. Since George Brett was a contemporary of Mario during Mendoza's AL days, it is conceivable that Brett would thumb through the Sunday edition of the Kansas City Star, checking to see which rivals had a lower batting average than Mario Mendoza. Most likely, this would have happened in 1979, since that was the only year that Mendoza's batting average truly hovered around the .200 range.

You know what's interesting about all this? No one questions the greatness of George Brett. He is, in my assessment, one of the 50 greatest ballplayers ever. How can anyone argue his credentials: a first ballot Hall of Fame selectee, member of the 3000-hit club, only man to win batting titles in three different decades and the closest approach to the holy grail of a .400 season in the last half-century. Yet, he is probably best remembered for three things:

Mexican sportscaster Oscar Soria corroborates the SI story. The voice of the Mexican League’s Hermosillo Naranjeros, Soria provided these comments concerning the Mendoza Line:

"I know Mario because he is the manager of the Obregon Yaquis in the Mexican Pacific League. I am a sportscaster in this league, I do the play-by-play of the Hermosillo team on TV, and that’s the reason I know Mario very well. In an interview a few weeks ago, I asked Mario about the Mendoza line and he said that Tom Paciorek was the first to mention the phrase ‘Mendoza Line’ when he read the Sunday paper. Then George Brett heard about that and, years after that, Chris Berman quoted about the Mendoza line. Mario said that when Chris Berman mentioned it and people started to laugh, he was angry, but now he enjoys the fame of the phrase Mendoza line.

Based on the statements of Soria and the Sports Illustrated article, we all can be fairly certain that the originator of the “Mendoza Line” were his own teammates and not an outsider like Brett.

How did the term, Mendoza line, become a piece of modern-day American jargon? The answer is intuitively simple: ESPN. The all-sports television network began its emergence right at the tail-end of Mario Mendoza's playing days. Without sounding too much like a sociologist, such a cultural influence ESPN Sportscenter has become, not only has it injected many new buzzwords and catch phrases into our everyday speech, it has even changed the way professional athletes play the game. Look at NBA basketball. The slam-dunk and the long 3-point shot are the only things you see highlighted on Sportscenter and its spawn. Basketball players, knowing the value in frequency of highlight file during contract negotiations, emphasize the perfection of these "circus shots" at the expense of say a 12-foot jump shot. This may explain why few players can hit a mid-range jump shot anymore and NBA teams seldom break 100 points scored in a game anymore.

It's not much different in baseball. The only things you see highlighted anymore are the home run, the strikeout and the bench clearing brawl after a hit batsman. Experts attribute the spike in recent home run hitting, in part, to the modern-day player's mentality of getting a few seconds of evening highlight film -- even at the expense of striking out more.

With such a cultural stranglehold on the American male population, it stands to reason that terms like, "Cooler than the other side of the pillow," "back..back...back..back...back" and "He's gone below the Mendoza line" take on lives of their own after you hear them day after day from Chris Berman et. al.

Another reason for the popularity of "Mendoza line," is that it just plain sounds

pleasing to the ear. Spanish is a pretty sounding language, especially those rich, rolling Z's. Men-doh-zzzzahhhh! For Americans, always looking for something cool and hip to say, "Mendoza line" is a sure-fire. Use it in a sentence and you're batting 1.000 in hipness!

The Mario Mendoza Story

It's worth our time to get to know the man who owns the most famous line since Mason and Dixon. I vividly remember Mario Mendoza as a rookie with the Pittsburgh Pirates. As a person who grew up as an ardent fan of the Philadelphia Phillies throughout the '70s, the team I hated with all the hate in the world was the cross-state Pittsburgh Pirates. Not only were they a natural rival, they always seemed to take pleasure in drubbing the Phillies until the Phil's finally got good enough (read Steve Carlton and Mike Schmidt) to return the favor. My recollection of Mario Mendoza back then was that he was a wonderful defensive shortstop and (at least in the games I saw or heard him play) hit no better or worse than one of my idols, Phillies shortstop Larry Bowa.

Mario (Aizpuru) Mendoza was born in Chihuahua, Mexico on December 26, 1950. The unusually named city (translates as “dry and sandy place”) is about 250 miles south of El Paso and serves as the capital of the largest state in Mexico. Chihuahua was also the birthplace of all-time minor league home run king Hector Espino and renowned actor Anthony Quinn.

While it is an exaggeration to say Mario Mendoza was born with a fielder’s glove on his hand, he must have excelled as an infielder at a very tender age. Oscar Soria saw Mario play throughout his career. He recalls this inspirational story of Mario Mendoza’s origins in professional baseball:

A guy named Noga was the manager in Hermosillo. Mario was a rookie. He was trying to be the shortstop. Mr. Noga told Mario, “You have nothing to do in baseball; you are wasting your time.” So Noga sent Mario to the Navojoa Mayos. [It was with this team] where he started to show his potential in this business and started his great career.

Mario Mendoza impressed scouts with his superior range, sure hands, fluid motion, and strong, accurate throws to first. Signed as a 19-year-old free agent by the Pittsburgh Pirates, Mendoza quickly showed his defensive prowess. Brian Barsher, who was also a shortstop on the Pirates’ 1971 spring training roster, recalled that Mario Mendoza’s quickness in getting to the ball and quick release in his throw were convincing enough to make Barsher move to catcher.

One of Mendoza’s earliest influences was the legendary Roberto Clemente. He worked out with the great Pirate outfielder during spring training sessions 1971 and 1972. Mendoza and other Hispanic minor leaguers would listen to Clemente’s prophetic advice on overcoming the hardships of making it into the majors. So enthralled Clemente became when talking to the prospects, he would oftentimes miss dinner and continue his lectures through the evening. Mendoza and Clemente might have been teammates, had Clemente’s life not been tragically cut short following a December 31, 1972 plane crash while on a humanitarian mission.

Mario Mendoza progressed well on his way up to the majors. He led Carolina League shortstops with 79 double plays for Salem in 1972. His high-water mark with the bat came in 1973. While playing Double-A ball at Sherbrooke, Mendoza posted career bests with 8 home runs, a .268 batting average, and 30 stolen bases. He was also named all-star shortstop of the Eastern League.

He joined the Pirates early in the 1974 season and hit .221 for them in 91 games. The Pirates of '74 won the NL East and faced the Dodgers in the National League Championship Series (NLCS), losing 3-games-to-1. In his only post-season action, Mario Mendoza made it into three games and had one RBI single in five at bats. Now isn't that interesting; his lifetime post-season batting average is .200. That's truly smack-dab on the Mendoza Line. But in those playoffs, Mendoza fared better than the following Pirates who had at least 5 at bats: Ed Kirkpatrick (.000), Al Oliver (.143), Dave Parker (.125), Bob Robertson (.000) and Rennie Stennet (.063). Dodgers' ace Don Sutton, with a 0.53 ERA in 17 innings work, pretty much kept most of the Buccos in check..

Mario Mendoza played with Pittsburgh through 1978, mostly in a reserve role to Frank Taveras. A solid and versatile defenseman, Mendoza played second base and third base as well as shortstop. Along the way, there were some interesting moments. In 1976, he hit a final inning double to beat the Houston Astros. Once, in 1977, he even pitched a couple of innings for the Pirates, giving up 3 earned runs in the effort. But what might have been the clincher to forever stay away from the mound was when a line drive struck him on the belt buckle, nearly depantsing him in the process. Mario hit his first Major League home run in 1978 against the San Francisco Giants.

Traded to the Seattle Mariners in 1979, Mendoza finally found himself in a starter's role. He appeared in 148 games as the everyday shortstop and batted .198 that year. This ties him with Steve Jeltz for most games played in a season while batting below .200. He did have some highlights at the plate. His only home run of the year was an inside-the-park shot. Against the New York Yankees on July 11, Mario went 2-for-4 with two runs scored and three RBI in a 16-1 Mariners' rout. He even led the team in an offensive statistical category -- sacrifice bunts with 13.

Tom Paciorek, the alleged author of the Mendoza Line, stated that Mendoza was one of the Mariners’ most popular players and was something of a clubhouse wag. Mendoza’s favorite target was the grizzled veteran Willie Horton. Though in his late thirties, Horton played every game at DH for the 1979 Mariners and clouted 29 home run balls. Mendoza was forever giving Horton a hard time on everything from his age to never playing the field. According to Paciorek, Willie Horton used to always say to Mario Mendoza, “Get away from me, you crazy Mexican.” Paciorek, while sitting next to a sleeping Horton on a bus ride, claims that the slugger woke up screaming, “Get away from me, you crazy Mexican.”

In 1980, while his nemesis, George Brett, made one of the closest charges to the Holy Grail of .400, Mario was on a quest of his own -- to break .300. On June 10, he homered and singled against Boston to raise his batting average to .287. Earlier, Mendoza hit safely in nine straight games and had a three-hit game. For a time, one had to be hitting extremely well to get over the Mendoza Line. Though he cooled off a bit at the end of the year, Mendoza still was something of an offensive force, dinging two home runs and a .245 average—both major league career highs. On defense, he was outstanding as usual. It's ironic that George Brett, who has given Mario Mendoza all the notoriety a person could ever ask for, recalls how slick-fielding Mario staved off Brett's chance for immortality:

"I remember going into a series in Seattle, think I went 2-for-12 with two home runs, but hit the ball on the nose like 10 times. It was one of those streaks. I remember Mario Mendoza, the shortstop for the Mariners, making two or three diving stabs up the middle. When that starts happening, you think, 'Geez, I wonder if it's in the stars.' You're hitting line drives right at someone and guys are diving for balls and catching them. You're like, "What is going on here? A month ago that was a hit." Now all of a sudden I can't buy a hit. Then you start trying a little too hard.

Part of an 11-player transaction with Seattle and the Texas Rangers, Mario Mendoza joined the Rangers for the 1981 season. Mario was elated over the trade, telling The Sporting News, “I know there are a lot of Mexican people in the Dallas-Fort Worth area, and that’s going to motivate me to play better.” Honed by a winter of Mexican League play, Mendoza was extremely sharp at spring training. He proceeded to beat out another shortstop hopeful in Mark Wagner for the starting spot.

During the strike-marred 1981 campaign, he enjoyed a good year for a good team. For a team whose infield defense was traditionally branded as “klutzy,” Mendoza’s consistently slick fielding was a godsend for the Rangers. He was also hitting in the .270s and delivering some clutch RBI. With Mario Mendoza hitting, Texas was surging to first in the AL West. They were just 11/2 games behind Oakland on June 12, when baseball’s longest labor dispute of the time curtailed nearly 40 percent of the season and dashed the Rangers’ hopes of their first title. Mendoza’s batting average also faded and he finished the year at .231.

Mario finished out his career with the Texas Rangers from 1981 to '82. In the end, Mario Mendoza had the following career batting statistics:

|

G |

AB |

R |

H |

2B |

3B |

HR |

RBI |

SB |

AVG |

|

686 |

1337 |

106 |

287 |

33 |

9 |

4 |

101 |

12 |

.215 |

Mario Mendoza hit under .200 in five of his nine seasons. But on Mario's behalf, in the four years he had over 100 at bats, he batted well over .200 in three of them and would have batted .200 in 1979 if he had just one more hit. In other words, had Mendoza been an everyday player, his career batting average would most likely have been in the Mark Belanger range (.228).

Could he have been a more dominant hitter? It is hard to say. He seemed big enough; at 5'11" and 180 pounds for most of his career, he had the same stature of Hank Aaron. He had decent speed as well. The one thing I do observe about Mario Mendoza is that even in his rookie days, he was wearing glasses, rather thick ones at that. When you hear Ted Williams' claims that his vision was so acute, he could see the stitches of an inbound Bob Feller fastball, perhaps Mario lost a few key milliseconds trying to lock-on to the baseball.

On defense, Mario Mendoza's career .961 fielding percentage is one of the 100 best ever for a shortstop (minimum 500 games played). To better get an appreciation of Mario's fielding ability, let's compare Mendoza's defensive numbers in his only true year as an everyday player, 1979, to those of the AL 1979 Gold Glove winner as shortstop, Rick Burleson:

|

PLAYER |

G/AB |

PUTOUTS |

ASSISTS |

DPs |

TC/G |

FA |

|

BURLESON |

153/627 |

272 |

523 |

109 |

5.3 |

.980 |

|

MENDOZA |

148/373 |

177 |

422 |

91 |

4.2 |

.968 |

While a cursory glance shows that Burleson has Mario Mendoza beat in all major defensive statistical categories, take a look at the at-bats column. As a less formidable hitter than Rick Burleson (5 HR/60 RBI/.278 BA in 1979), Mario Mendoza was often pulled out of games early for a pinch-hitter. A rough estimate determines that Mendoza played only 75% of the total innings Burleson played. Had Mario Mendoza played an equivalent amount of innings, his assist, double play and total chances per game totals would have been significantly higher than Rick's. Total Baseball also recognized that fact and gave Mendoza an overall higher defensive rating than Burleson that year and the third highest in the entire Major League. In a 1979 article entitled “M’s Singing Praises of Mendoza’s Glove Magic,” appearing in The Sporting News, Seattle beat writer Hy Zimmerman wrote how the pitchers were praising the amount of runs Mario Mendoza saved them. Hall of Fame second baseman Bill Mazeroski, a coach for Seattle that year, commented, “Mario Mendoza is the best shortstop in the American League.” “That’s praise from Caesar,” added Zimmerman. TSN later featured a fairly prominent photo of Mendoza in the midst of executing a rather spectacular 4–6–3 twin killing. On defense, Mario Mendoza was among the elite.

After his major league career, Mario continued to play professional baseball in Mexico, batting .291 during seven seasons in the Mexican Summer League. Mendoza also played 18 years of winter ball in the Mexican Pacific League before, during, and after his career in the “Great Leagues,” as the Mexicans refer to our major leagues. Representing his country in five Caribbean Series tournaments, Mario performed with great intensity and emotion, with Mexico’s national pride at stake. While playing in the Mexican Leagues during the mid-1980s, Mario Mendoza was the league’s equivalent of Derek Jeter. As Mario Mendoza’s son recalled during an interview, his father was nicknamed “Elegante.” Women appeared in droves at games, as much for Mendoza’s good looks as his grace in the field. They compared him to a ballet dancer. He even had groupies. In 2000, Mario Mendoza received the ultimate honor of immortale by his countrymen. He was elected into the Mexican League Hall of Fame (Hall FAMA), the “South of the Border” equivalent to Cooperstown.

After his playing days, Mario Mendoza remained active in professional baseball. He has scouted in Mexico as well as managing in the California Angels' minor league system from 1992 to 2000. Mendoza managed as high as the AA-level while with Midland of the Texas League; five times he has led teams he has managed into the playoffs. His most recent assignment was manager for the Lake Elsinore Storm of the California League. He had the opportunity to manage his son, Mario Mendoza, Jr., a promising minor league pitcher. His career managerial record, as of the completion of the 2000 season, is 579–662.

Fans who have seen Mario Mendoza in the minors describe him as one of the friendliest people in baseball. He actually comes over and talks to fans before ballgames. However, the one thing about the Mendoza Line is that you don't want to use the term around Mario. While Mario Mendoza was managing the Angels' farm team in Palm Springs in the early '90s, someone wrote about him going after a fan who was making light of his hitting. As Mendoza pointed out at the time, he was a highly regarded hitter in Mexico (batted .291 in 660 games over seven seasons as a Mexican Leaguer).

In another episode, while Mario Mendoza was managing the Cedar Rapids (IA) Kernels of the Midwest League in 1997, a player from the opposing Lansing Lugnuts hit one deep that went above the wall in right field and came back. The right fielder claimed the ball tipped off his glove and he caught it on the way down for an out. The radio announcers thought it bounced off the fence and should have been ruled it a double. However, the umpires called it a home run. In a rare display of fury, Mario Mendoza rushed out of the dugout and argued the call vehemently at Darwin Schiltz, the bases ump. After Mario kicked and threw dirt at the myopic arbiter, a la Billy Martin, Schiltz ejected Mendoza.

In the final analysis, Mario Mendoza batting statistics may not support the claim that he was an asset to a team. But consider this. In his five years with Pittsburgh, the Pirates were a division champion twice and division runner-up three times. Prior to Mario's trade to Seattle in 1979, the Mariners finished 56-104; with Mendoza as the everyday shortstop, the Mariners improved to 67-95 and out of the AL West cellar. When he arrived in Texas for the '81 season, the Rangers were coming off a sub-par year; Mendoza takes over as shortstop and Texas finishes in second place, just 5 games behind Oakland. I don't think this is total coincidence; I do think sure-handed infielders are an important building block to a successful team. He is truly Pittsburgh's original "SUPER MARIO"

MENDOZAMANIA: ESSENTIAL MENDOZA LINE TRIVIA

Other Links of Interest:

![]()

![]() Society for American Baseball Research (SABR)

Society for American Baseball Research (SABR)

![]() John Vukovich: Another website by the author

John Vukovich: Another website by the author

![]() Bill Plummer: Another website by the author

Bill Plummer: Another website by the author

![]() The Bill Bergen Shrine: An award website by the author

The Bill Bergen Shrine: An award website by the author

I hope you found this web page of interest. Please post your comments or any additional anecdotes, facts or other info with respect to Mario Mendoza.

e-mail "The Author" at:

If you liked this piece, you'll love Mendoza's Heroes: Fifty Player's Below .200, Al Pepper's sensational new book. Published by Pocol Press.

Link to www.mendozasheroes.com